Exploring the Politics of Gender Representation on Instagram:

Self-representations of Femininity

Authors: Sofia P. Caldeira PhD, Sander De Ridder PhD and Sofie Van Bauwel PhD

Source: DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2018), pp. 23-42

Published by: Leuven University Press

This article presents an analysis of the politics of gender representation on Instagram. It adopts a broad understanding of the political in terms of “everyday politics” and “everyday activism”. This allows for exploring the political potential of self-representation on Instagram and Instagram’s ability to enable more diverse forms of gender representation. It starts from the assumption that Instagram can play a role in reproducing and reinforcing traditional gender norms, and then explores the technological affordances and limitations that shape representations, such as Instagram’s Terms of Use and the diffuse power exerted by Instagram users’ feedback. These theoretical arguments are illustrated by discussing the recent ban of Marisa Papen, a popular Instagram model.

Gendered Instagram Struggles: The Banning of Marisa Papen’s Instagram Account

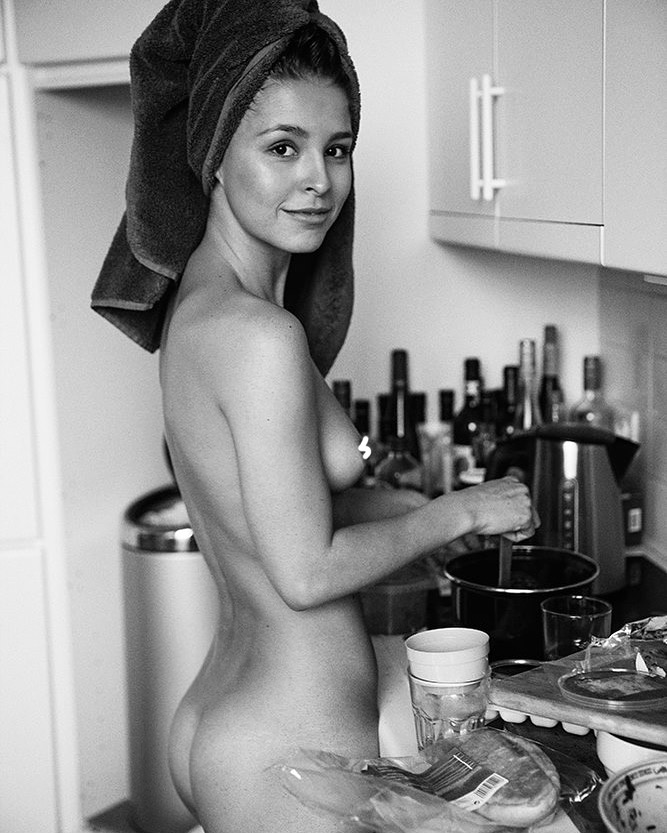

Marisa Papen is a twenty-four-year-old Belgian Instagram model, who gained national and international fame by sharing carefully aesthetically crafted photographs of her (nearly) nude body on Instagram, in an unapologetically sexy manner. Before being banned in 2016, Papen’s Instagram account had amassed over seven hundred thousand followers. She was even voted the “most beautiful woman on Instagram” by the readers of the Dutch online magazine Manners.nl. For Papen, Instagram played a significant role in launching her modeling career by serving as a tool for sharing her stories and for making connections with a wider audience.

Marisa Papen is from Belgium, a liberal western European country. However, her Instagram and modeling activities transcend this local context. She was featured in magazines and websites worldwide, including in shoots for both Playboy.com and several other cross country Playboy issues . She posed for photoshoots worldwide, and her Instagram had a large transnational group of followers. Despite her wide popularity, Papen’s photographs were deemed “too provocative” by Instagram, and her account was thus banned from the online platform in August 2016. This decision made by Instagram – a private company based in the US – creates a transnational context, transcending the local Belgian context. More importantly, it brings the “platform politics” that shape Instagram use to the fore. For Papen, this was the fourth time her account was banned from Instagram. But unlike the previous times, when her account was quickly re-instated after making an appeal to Instagram, this was a lasting ban, which was still in effect at the time of writing this article, over three months later. Papen’s example thus provides an illustration of the theoretical discussion previously introduced and exemplifies how gender politics work in relation to her Instagram account ban.

Papen’s Instagram use is quite distinct from the informal engagement of most common social media users, as it is not confined to the expected practices of selfie-taking. Papen’s Instagram use is better understood in line with Leah Schrager’s conceptualization of the uses of this social media platform by Instagram models, which entails a highly skilled labour of self-branding; a shaping of one’s own image and Instagram practices, in order to gain fame, to spread one’s perspective, and to monetize one’s Instagram activity. Nonetheless, Papen’s illustrative case helps to emphasize the complex and nuanced gender representation politics that underlie and shape all self-representation on Instagram.

The banning of Marisa Papen’s Instagram account makes particularly clear that there are institutional constraints at play on Instagram. These reflect the specific “platform politics” of Instagram, which are shaped by the ideologies and commercial interests of Instagram. These institutional filters are made explicit, for example, in Instagram’s Terms of Use (2016), which prohibit the sharing of images depicting full or partial nudity, of photographs with sexually explicit or pornographic content, as well as content of a violent, dis- criminatory or illegal nature. Papen had carefully avoided violating the terms imposed by Instagram by finding creative ways to evade the limitations. She used strategies of creative censorship, sharing photographs in which she carefully covered her breasts and pubic area by posing in a certain way or by using props, or by playfully using emojis and other drawings to cover her nipples and other body parts deemed “too explicit”. These strategies of creative censorship can still be seen on Marisa Papen’s Facebook account (Papen, 2017), in photos such as her current profile picture, a nude portrait of Papen, in which one of her nipples is covered with her own hand and the other with a drawing of a white heart.

Despite such creative efforts, her Instagram account was still banned. Marisa Papen has never publicly shared any official reply she received from Instagram about previous bans. Yet the response of the platform seems to echo other similar cases when Instagram banned certain images due to what they deemed inappropriate, only to publicly concede later on that they “don’t always get it right when it comes to nudity”, acknowledging their mistakes and restoring the banned photographs and accounts.

Papen tried once more to appeal Instagram’s decision and to have her account reinstated, but at the time of the writing of this article, her account was still not re-activated and she had not shared any response from Instagram on her other online platforms, such as her website or Facebook account. Marisa Papen’s gendered self-representations are actively created through a negotiation with Instagram’s possibilities and limitations. On Papen’s blog and in interviews, she has explained the aesthetic of her nude photography as a discourse of agency and resistance – one that is very different from the justification given by Instagram for her ban. Instagram argued that her pictures were too provocative and too sexually explicit. Papen, however, sees herself as a “free, wild hearted expressionist” (Papen, 2016a), using her photographs as a means to express her way of viewing the world. Her choice to “go naked” is presented as a form of resistance, and, simultaneously, as the way in which she simply feels comfortable expressing herself. She equates it with an effort to distance herself from the “corruption of society”, that is, as a mode of being that is authentic, pure, and in touch with nature (Papen, 2016a). It is a nakedness that she claims has no specific bodily requirements, that supports embracing the body just as it is, and that encourages feeling good in one’s own skin.

What Is Political About Gender Representation on Instagram?

Papen’s discourse echoes the political discourses of liberation and empowerment of “fourth-wave feminism”, although she does not actively engage in overt digital feminist activism or make use of politicized self-representation. She takes advantage of the online platforms of Instagram and her own blog to create representations that seek to disrupt the hegemonic limitations of “proper” femininity. Furthermore, Papen’s use of Instagram embodies the notions of “everyday politics” and “everyday activism” that view the sharing of women’s personal representations as political in itself, even when not deliberately constructed as such. It is a “micro-political practice of daily life” that allows for the dissemination of different perspectives and discourses. By using Instagram, Papen claims visibility, making her voice heard and using the humanizing potentialities of self-representation to present herself as a “speaking subject” in her own right. The photographic practices of Papen on Instagram seem, in this way, to be following the postfeminist idea of bodily display as being a sign of strength, independence, and empowerment.

In addition, by using Instagram, Papen seems to be claiming agency not only over her photographic practice but also over her modeling career, adopting an ethos of self-enterprise, self-employment, and self-branding. She subverts the traditional power structure of the professional modeling agency and media industry, taking matters into her own hands, doing the work of production, distribution, and networking herself, and monetizing her Instagram activity.

Despite the aforementioned institutional constraints of Instagram’s Terms of Use, which ultimately led to Papen’s account ban, there is still a sense of agency and freedom of self-representation present in Papen’s discourses and photographs. Papen’s discourses and photographic practices seem to echo the cautious optimism surrounding the political potential of Instagram’s self-representation by opening up a space for a more diverse representation of gender.

However, the same sceptical and tentative approach that is required in the study of Instagram must also be extended to the present case of Marisa Papen. The discourse surrounding her photographic practices seems to frame Instagram as a platform where everybody can become a successful model, even those who do not fit the typical high-fashion standards. Yet this narrative overlooks the emphasis put on the representation of Papen’s own body in a highly conventional and idealized manner. Her body and photographic representations still visually comply, point by point, with the “young, white, able-bodied, middle-class, apparently heterosexual and conventionally attractive” standards that Rosalind Gill exposed as comprising the exclusionary view of women in traditional mainstream media. Her self-representations occupy a privileged position, benefiting from the visibility generally afforded to representations of women of her race and cultural context. One must keep in mind that intersections with race, religion, sexualities, cultural context, etc. shape the readings that are generally made of such self-representations, and that representations of women who, unlike Papen, do not comply as neatly to the beauty standards, either by virtue of their race or body size, for example, tend to face more online harassment, “flagging” and “reporting” by other users, rather that being hailed by the media as the “most beautiful woman on Instagram”.

In line with other recent studies on self-representation on Instagram, Marisa Papen’s photographs can also serve to reproduce normative gender representations through her poses, styling, mannerisms, and a portrayal of sexiness that is traditionally constructed as enticing to the male gaze. Perhaps inadvertently, she continues to represent the same formulaic gender stereotypes, while claiming empowerment. Equating this very narrow definition of “sexiness” with empowerment leads to the internalization of oppressive norms of femininity that perceive the female body as both powerful and in need of constant improvement. Despite her stated views that there are no specific bodily requirements to be an Instagram nude model, Papen nonetheless adheres to and professes a specific fitness and dietary regime in order to maintain her slim figure. Even under the banner of something done just to please oneself, the representations are still strikingly similar to the conventions that the larger society identifies as “sexy” femininity states, through a process of interpellation, these social representations have become accepted by Papen as her own authentic representations. Despite Papen’s claims of resistance, her self-representation can be read as one that has already been “absorbed by the mainstream” and has become tailored to normative tastes. Her images draw their influence from other societally approved images, intertextually linking them to the texts and conventions of popular culture. They represent a highly perfected and idealized image of femininity, filtered both visually and through cultural conventions.

Conversely, the edginess and the resistant potential of Marisa Papen’s self- representation on Instagram has also been absorbed and incorporated into the popular mainstream media. Her images are still constructed in a way that is especially attractive to the male gaze, appealing to a traditional heterosexual male audience, as an erotic object for male visual pleasure. This erotic appeal to a heterosexual male gaze is reflected in the comments that often accompany Papen’s photographs. Although the original comments on her Instagram account were removed when her account was banned, on her other online platforms, such as her website (Papen, 2016) and Facebook account (Papen, 2017), most comments are made by male commenters. These comments are mostly positive and supportive, expressing appreciation for the aesthetics of both her photography and her body, often echoing her own discourses of freedom and naturalness. Yet, at other times, the comments have an explicitly sexual nature, expressing overt desire for Papen herself. As such, Papen’s images could be seen not only as highly gendered representations but also as sexualized. She represents herself as fitting the seemingly hetero sexual ideal. These images are produced for male sexual pleasure.

Indeed, Papen’s images, with their appeal to a conventionalized notion of sexiness expressed in the poses and styling, can evoke concerns of sexual objectification of women. Viewed in isolation, they seem to encompass some of the characteristics that Martha Nussbaum associates with objectification. Namely, the notions of instrumentality – of treating a woman as a tool for the purposes of others, in this case as a tool for achieving visual and erotic pleasure – and the denial of subjectivity – treating women as if their subjective experiences and feelings do not need to be taken into account. As a result, Papen is often featured in media outlets typically associated with sexism and objectification, such as Play- boy magazine or the Belgian online “lads magazine” Clint.be. Some of the people commenting on Papen’s blog were quick to point out these inconsistencies, stating that “if you look at her actual images, the way they’re photographed, and the initial sneer at Playboy etc. for objectifying women: you really have to ask what the difference is. 99.9% of people looking at her images just see another beautiful model in semi-erotic nude poses...”.

The self-representations of Marisa Papen can thus be seen in disparate ways, both as artistic and personal self-expression and as erotic or near-pornographic imagery displayed in objectifying media outlets. Such porous borders were similarly questioned and contested by Sarah Smith in light of the case of Natacha Merritt, an American photographer whose online photographs of her own sexual encounters were temporarily categorized as works of art. The case of Natacha Merritt relies on discourses similar to the ones used by Marisa Papen in defending her photography as a vehicle for self-exploration and emphasizing her agency in creating images. However, unlike Merritt’s often-explicit images of sexual acts that can be closely linked to pornography, Papen’s images occupy a more tentative position. They also rely on a voyeuristic and objectifying gaze, but they remain closer to an erotic aesthetic and are framed by her personal discourse of resistance and freedom of representation.

There is also a clear gender bias underlying Marisa Papen’s ban from Instagram. The platform’s Terms of Use are quite vague with regard to the nudity policy, relying on somewhat ambiguous divisions between appropriate and inappropriate body representations. Representations of women and men carry different meanings, and thus they receive different treatment from Instagram. While Instagram accounts filled with topless and nude men abound, with some in quite provocative poses (e.g. male models like River Viiperi, Drew Hudson, and Terry Miller), male nudity tends not to be perceived as heavily sexualized; rather, it is viewed as neutral or functional, and is thus not seen as a cause for “reporting” and bans. Conversely, female nudity is quickly equated not only with sexuality but also with depreciative notions of vulgarity. In terms of overtly sexy representations of women, there seems to be an excess of “social puritanism” that rules over Instagram, leading to accounts being banned even when they do not directly break Instagram’s rules, thus limiting the potential for radical visibility.

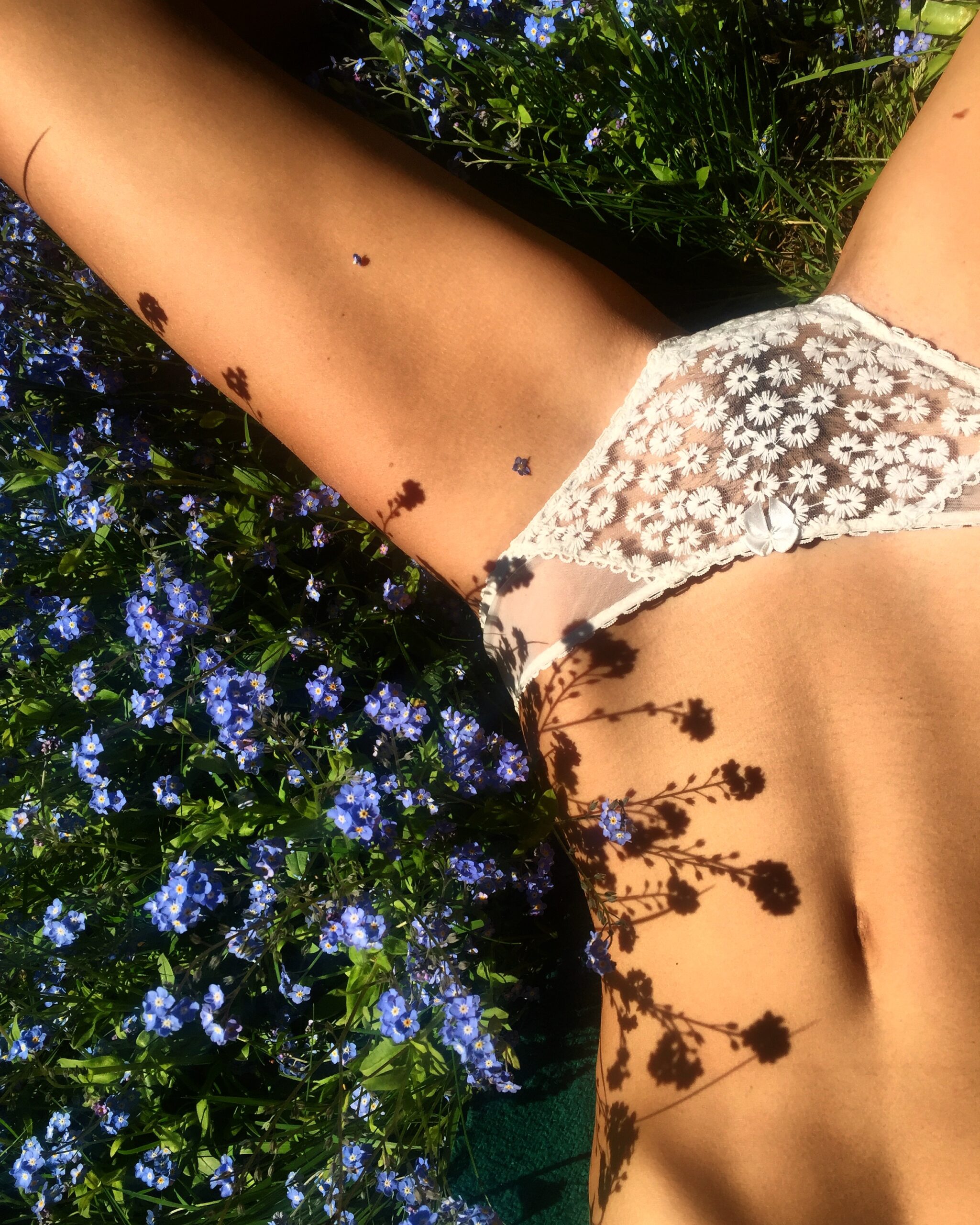

As the 2013 polemic surrounding photographer Petra Collins demonstrates, this online puritanism is not confined to the cases of representations that are too explicitly “sexy”. On her Instagram, Petra Collins shared a photograph of herself from the waist down, wearing a bikini, against a sparkly background. The photograph might have gone unscathed if not for the fact that her bikini line was ungroomed and, as such, there was some visible pubic hair. Consequently, she was banned from Instagram. As Collins herself noted, her image in no way broke the Terms of Use policy, as it contained no nudity or pornography. This example emphasizes the inconsistency of Instagram’s policy, for while plenty of more revealing images of women in bikinis are allowed on the platform, Collins’ photograph was censored for showing an image of a female body refusing to adhere to the dominant, narrow feminine ideal.

These controversies illustrate the ways in which the practices of self-representation on Instagram are embedded in broader discursive practices that serve as a means of regulating and limiting the photographic practice. These discourses are used to impose discipline by defining what is and is not appropriate to show (e.g. explicitly sexy photographs of women).

The power underlying Instagram’s “platform politics” and gender representation politics is not, then, a “top-down” power. Its power is not enforced by some sort of iron hand that selects and bans all the photographs and accounts considered inappropriate according to its Terms of Use. Rather, it is a more diffuse and unbounded form of power that is spread across its whole user base, with the banning of some accounts being triggered by the users who “flag” and “report” the images for being inappropriate. Users’ scrutiny and judgements, in the form of “likes”, “comments”, “flags”, or “reports” serve to regulate Instagram’s gender representation, punishing those representations that stray too far from the desired norms.

The case of Marisa Papen becomes more complicated when considering that many, perhaps even most, of the photographs she shared were not self-representations in a literal sense but, rather, photographs of herself taken by others, often in the context of professional modeling shoots. The fact that the photographers in such sessions tend to be male contributes even more to the sense of empowerment and resistance claimed by Marisa Papen, to be viewed as a sort of disillusion. These images – created by male photographers for outlets like Playboy, and representing Papen in ways that can be read as traditional female objectification for male visual pleasure – can appear to fall back into the commonly established mainstream media practice of portraying women through the male gaze, although this is not Papen’s own view.

Indeed, Papen herself has been quite critical of this, embracing the ethos of self-representation that seems to define Instagram, and challenging the views of her photographs as male-imposed objectification. Even when confronted with the problematic choice of posing for Playboy, she defended this choice by framing it as an artistic expression of nudity and as a representation of her own, true, natural self. She has been vocal about her dislike of the objectification of women by the media, and has even acknowledged the role Playboy itself plays in this objectification. Nonetheless she countered that Playboy had offered her “total freedom of content”. As Nussbaum states, “in the matter of objectification context is everything”, and Marisa Papen views her work with photographers, in this and other sessions, as a collaborative effort, through which she gets the chance to express to a larger public her alternative and resistant views on nudity. Her agency is framed as a means to subvert the idea of objectification and to emphasize the experience of the individual, subjective self.

Although Marisa Papen’s use of Instagram is not confined to the expected practices of selfie-taking, she nonetheless embraces its self-representation ethos. The fact that these specific images have been actively chosen by Marisa Papen herself to be shared on her Instagram makes them, at some level, self-representations. They fit into a broader understanding of self-representation in terms of curatorial agency and choice about what to share. As Rachel Syme states, allowing someone else to take your picture and then posting it to Instagram is still a form of carefully chosen “myth-making-via-imagery”. As already stated, we can choose to represent ourselves in various different ways on social media, either by using self-portraits or photographs of us taken by others, or even by sharing photographs of things we love, like our pets or family. In this manner, the photographs of Marisa Papen taken by others are used to convey a more comprehensive sense of self-representation on Instagram, as she is an active participant making choices about what to show or to conceal. Overall, the study of Marisa Papen’s photographic practices on Instagram serves to complexify and question our understanding of the politics of gender representation on Instagram and to put into question the role of social media in shaping self-representations. Papen’s practices and discourses reveal a deeply nuanced stance on an ever-shifting middle ground between empowerment and compliance with the objectification of the male gaze. The possibilities of freedom are always accompanied by constraints in a precarious balance between resistance and conformity.

Conclusion

Although the case of Marisa Papen is a unique and non-generalisable illustration, it nonetheless provides an interesting real-life context that facilitates questioning the gender representation politics of Instagram and contemplating how this can affect the freedom of self-representation. The banning of Marisa Papen’s Instagram account was motivated by her (near-) nude photographs, which were deemed “too provocative” by Instagram. This decision makes explicit the institutional limitations and constraints that condition the potential uses of Instagram. The example shows how the platform’s specificities and its technological affordances – particularly Instagram’s Terms of Use and the way users can use the features of “flagging” and “reporting” as a form of diffuse power – can help to enforce these institutional policies. These institutional constraints shape, frequently in less noticeable ways, all self-representation on Instagram, punishing those representations that stray too far from the desired norms. Thus, every representation is the result of a constant negotiation between Instagram’s possibilities and its limitations.

The example of Marisa Papen also illuminates the tensions between Instagram’s political possibilities of resistance against hegemonic gender norms and its potential to reproduce and even reinforce traditional gender stereotypes. Her personal discourse is one of resistance and freedom of representation that echoes the political claims of “fourth-wave feminism” and of “everyday activism”. It reflects the optimistic views on Instagram’s political potential of self-representation to potentially produce more diverse, individualized representations. Yet Papen’s actual representations very closely resemble the hegemonic gender norms, reflecting the intertextual influence of popular media. Her case exemplifies how such representations can be absorbed by the media and are re-shaped into depoliticized media products. As such, her representations can serve as a means to reproduce and reinforce hegemonic gender norms under the deceptive banner of empowerment.

The complexities and nuances of Papen’s illustrative case are reflective of the practices of Instagram on a larger scale. This presents an opportunity to question how Instagram and its gender politics shape people’s self-representations and how people come to understand complex questions of gender. As Instagram becomes increasingly prevalent and embedded in our quotidian existence, redoubled critical attention must be given to these self-representation practices, which are deeply intertwined with broader questions of gender representation politics, even if they are often dismissed as narcissistic and trivial.

Authors:Exploring the Politics of Gender Representation on Instagram: Self-representations of Femininity

Author(s): Sofia P. Caldeira, Sander De Ridder and Sofie Van Bauwel

Source: DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2018), pp. 23-42

Published by: Leuven University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.11116/digest.5.1.2

Sofia Caldeira is a PhD student at Ghent University, conducting a project on representations of femininity on Instagram and women’s glossy fashion magazines, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT).

Sander De Ridder is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) at Ghent University, conducting research on the mediatization of young people’s intimate sexualities.

Sofie Van Bauwel is Associate Professor at the Department of Communication studies at Ghent University with expertise in research on gender and media.